Speaking is more than Speech

-Sydney Euchner, MS, CCC-SLP

It’s not uncommon for families to think to themselves, my child is a baby, they shouldn’t be speaking yet, they don’t need speech therapy. Or they may think, I can understand everything my child tells me, so why would I need to have a speech evaluation done? The reality is, speech-language pathologists support a wide range of communication skills and speaking consists of much more than just speech.

Another common misunderstanding is that speech and language can be used interchangeably to describe a child’s skill areas. Sure, a child may have impairments in both speech AND language and underlying impairments in one area may affect the other but what’s important to know is that these are two very different developmental domains.

So what does a speech-language pathologist do?

They work with individuals in all stages of life from birth through adulthood.

They work in a variety of settings including hospitals, nursing homes, schools, home health, outpatient clinics and private clinics.

They support individuals with a vast range of needs including: developmental disorders (speech impairments, delayed talkers), genetic disorders (Down Syndrome, Cerebral Palsy, Autism), Acquired disorders (brain injury, stroke), degenerative disorders (ALS, dementia), Voice Disorders (vocal-fold nodules, strained voice) and Feeding/Swallowing Disorders (infant feeding, impairments in swallow function after a brain injury or stroke). Plus, many more!

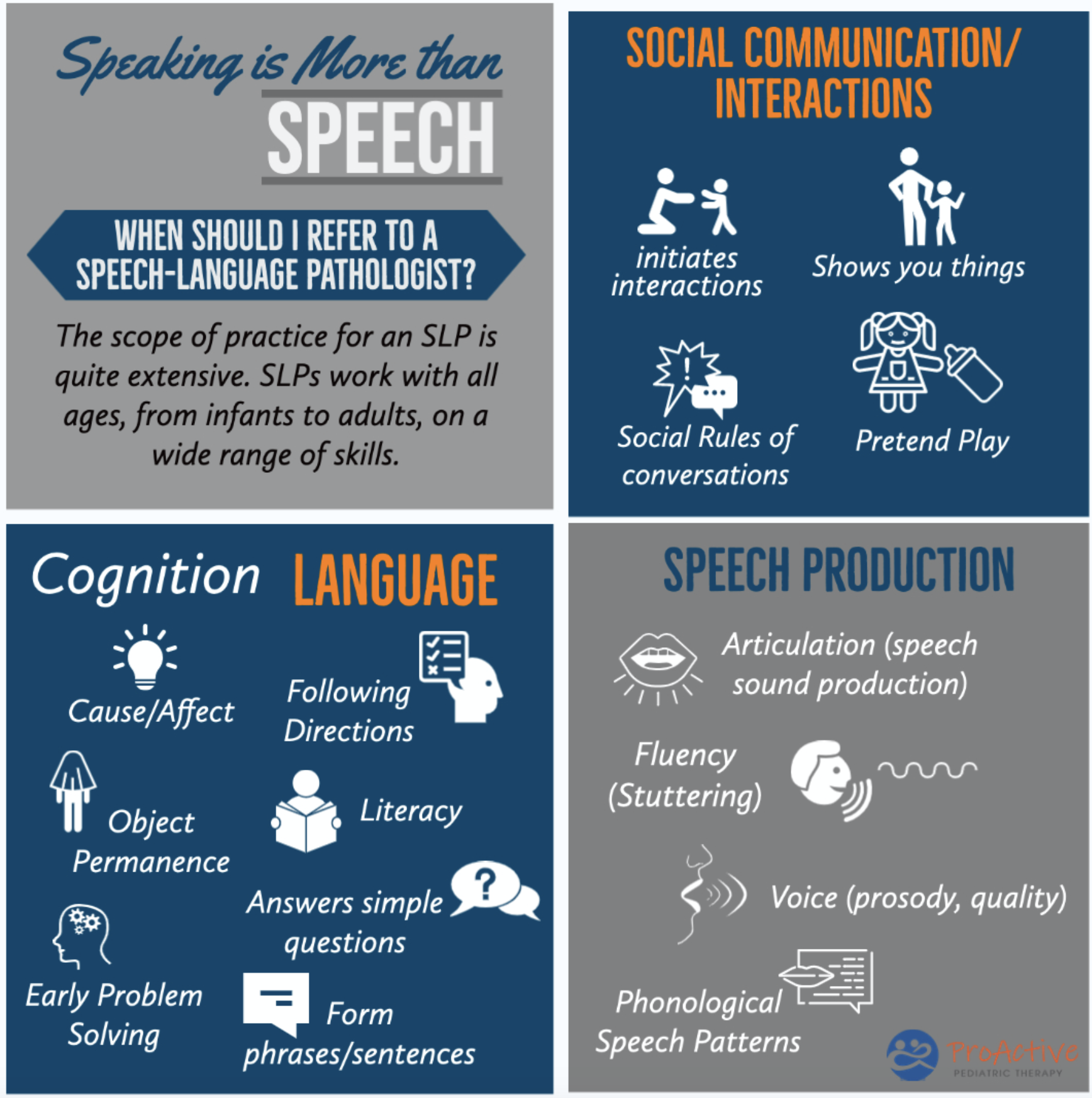

Below, you will find further information on the large 3 overarching skill areas that speech-language pathologist assesses and treat. It is likely that you will come across certain skill areas that may have never triggered you to consider reaching out to a speech-language pathologist. As I mentioned earlier, speaking is so much more than just speech. If you do have concerns, or even questions about any of the skills listed below, please do not hesitate to reach out! We would love to support you and your family. We love helping children and their families THRIVE.

Social Communication/Interactions (Pragmatics)

AKA, the foundation for language and all future learning. All communication begins with interactions between two people.

A child must pay attention to people, listen to what they say, initiate contact with people and enjoy playing together and sharing experiences before they are able to understand and use words.

Early Years

Seeking out and responding to other people is a skill we want to see develop in infancy. We want to see babies:

enjoy watching other people – particularly their faces.

Smile, laugh, and get excited when you talk to him/her by the time they reach 6 months old.

Even though they’re busy by nature, toddlers with typically developing language skills are not difficult to engage. Toddlers should:

include you in their activities.

show you things.

try to direct your attention to look at them.

look back and forth between you and a toy as you play together.

smile at you with frequent and easy eye contact.

Play skills – early pretend play (pretending to feed a baby, pretending to mop the floors) and symbolic play (pretending a spoon is a phone)

As children get older, they learn the social use of language consisting of knowing what to say, how to say it and when to say it.

Nonverbal communication like eye gaze, posture and facial expressions

Humor

Volume/Prosody/Tone of Voice

Repairing breakdowns (when someone does not understand you)

Code switching (shifting the way we talk between our friends and an adult such as our teachers)

Rules of Conversation: Topic maintenance, Interruptions, dominating a conversation etc.

Language

Consists of socially shared rules (grammar, vocabulary, symbols, etc) for how we use words to communication our thoughts

Cognitive Language/Receptive Language - Receptive Language and cognition are crucial because until a child learns to understand words, he or she is not ready to use those words to communicate. A child must understand words before he or she can say words.

Cognitive Skills – during that first year, a baby learns to understand how the world around them works. They learn routines and when to expect things to happen in their day. They learn:

Object Permanence: objects don’t disappear even though they can’t see them

Cause/Effect: They can make things happen by controlling certain things in their environment

Early Problem Solving: when they become more skilled at moving their body, they learn they can get things and make things better for themselves

Sustained and Divided Attention

Cognitive Skills – as children get older:

Executive Functioning: organizing and planning

Sequencing of actions, routines and events

Immediate short-term and long-term memory, working memory

Receptive Language Skills – Refers to what we can understand. For young children, this can include:

following directions (go get your shoes)

pointing to named pictures in a book or locating a toy you requested

Identifying body parts

Understanding of simple questions (Where’s mom? Who’s that?)

Answers Yes/No questions

Understands location concepts such as in, under or on top and understands size concepts such as small/big.

Receptive Language Skills as children get older:

Story comprehension (Who was the character in our book, where were they at in our story, what was the problem etc)

Sequence multi-step tasks

Understand what words mean, learn new vocabulary by comparing to what they already know

Follow multi-step directions

Expressive Language – How we use and combine words, gestures and symbols to share thoughts, ideas and communicate wants and needs

Early Years: communicative intent develops, which is when we see that our child is trying to communicate with you or tell you something. This starts with crying intentionally or whining, then they advance to vocalizing more purposefully such as grunting or using single syllable sounds that sounds like commands. (“Da!”)

Purposeful gestures: by 12-months, children may use gestures such as reaching towards you or directing your actions. These kind of body movements turn into real gestures that we recognize as communicative, such as waving bye-bye, blowing a kiss or pointing to get you to look at something.

Children develop vocabulary by first learning single words. Once a child has approximately 100 different words within their total vocabulary, they may start combing words into phrase.

Word combinations: by age 2, children should be consistently combining 2-words and by age 3, they should be consistently using 3-word phrases

As children get older: the “how” we combine words and use them to communicate our wants and needs continues to expand

Vocabulary continues to grow

Syntax – the rules of how we arrange and order words to generate a well-formed sentence

Grammar (regular/irregular past tense word forms, present/future tense, pronoun usage)

Formulating a narrative – retell a personal story or a story they heard by including relevant details and facts in a coherent sequence so that the listener understands

Speech

The actual production of sounds. This is HOW we use our voice to communicate our thoughts

Articulation – the ability to produce specific sounds such as saying “Tat” for “Cat” or “Wabbit” for “Rabbit”

Voice – The quality of the sound we produce. This consists of pitch, loudness and resonance

Fluency – Also known as stuttering, refers to the smoothness and rhythm of speech

Most toddlers substitute sounds and simplify words as they learn to talk. Many children will continue to substitute later developing consonant sounds (r, l, th) until they’re 6 or 7.

Even when a child’s speech contains some sound errors, a parent should understand at least half of what their 2-year-old says and nearly all of what their 3 year-old says. We do not expect unfamiliar adults to understand 100% of what a child says until they reach closer to 5. Even then there may be some sound substitutions.

When a child talks in what a parent might call “his own language” or uses long strings of unintelligible speech, this is jargon. Jargon is a part of normal expressive development, but when jargon persists past age 2 and the child is not using very many single words you do understand, this is usually a problem related to language development rather than how a child pronounces words.